The food system and planetary health

By Isabelle Sadler

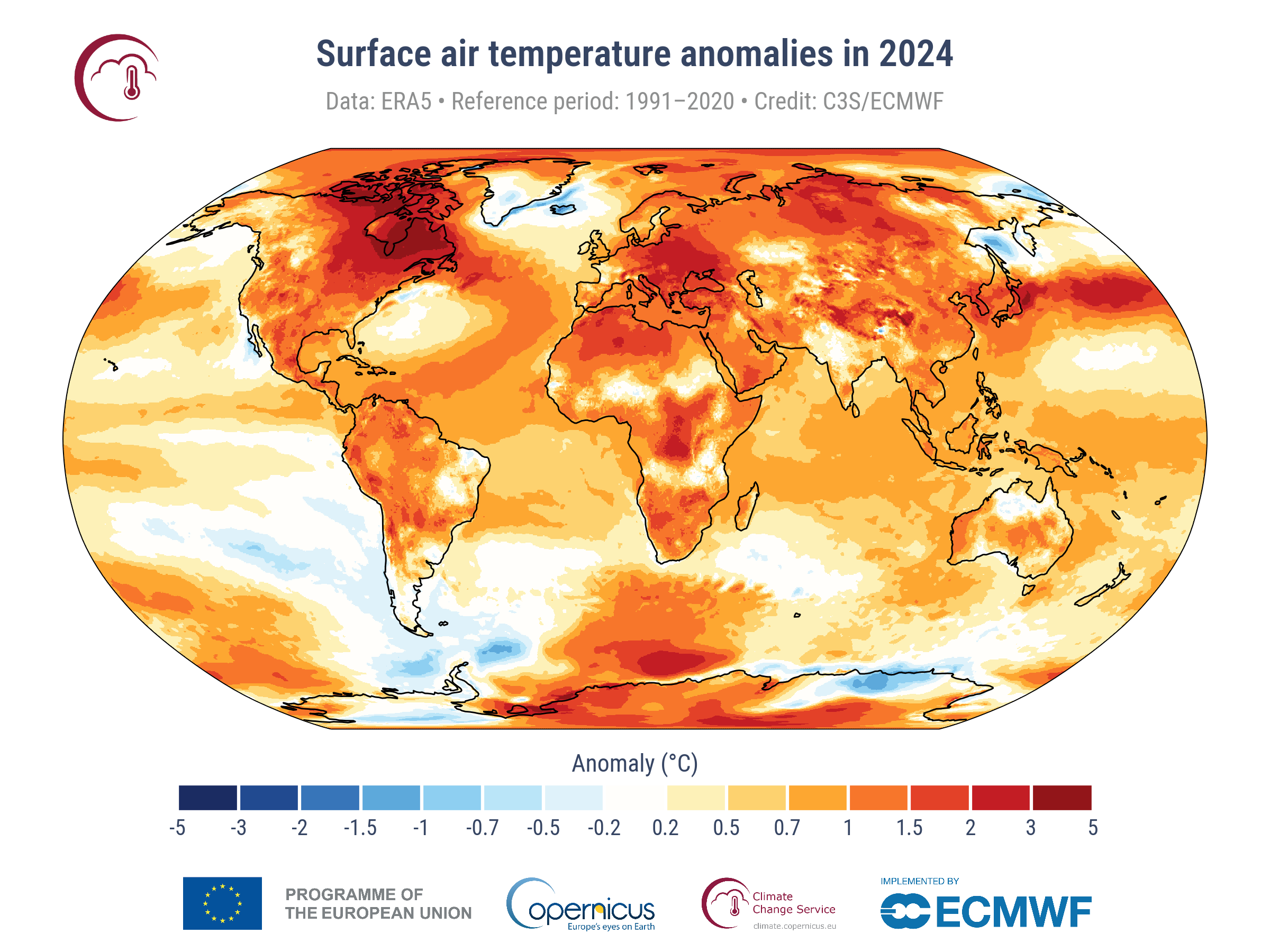

The climate crisis is a health crisis. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that the projected global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels could happen within the next decade – 2024 was the first year to exceed this level. The consequences of rising temperatures are already being seen and felt globally, with more extreme heat, wildfires, more frequent floods and droughts, rising sea levels, species loss and extinction and risks to human health, food security, water supply, livelihoods, and economic stability.

We cannot meet our climate and nature commitments, and safeguard our future, without changing food production and consumption. Even if fossil fuel emissions were eliminated immediately, the global food system alone would make it impossible to limit warming to 1.5°C. There is a clear consensus that a global shift away from animal agriculture towards a plant-based food system is a critical part of this change. Healthcare professionals should be leading by example, and supporting patients and communities to adopt healthier choices that will improve their quality of life and those of future generations.

The food system is at the centre of many global crises

Our food system lies at the centre of four urgent global crises: health, climate, biodiversity and soil. Current global food production is degrading soil, destroying natural habitats and contributing to species extinction. Agriculture is also a major driver of climate change, water pollution, ocean destruction, air pollution, land degradation, deforestation, and the loss of wildlife and biodiversity. The food system is responsible for roughly a third of all greenhouse gas emissions. Beyond environment and health, there is also a fifth, ethical crisis. Our food system harms both people and animals and keeps nearly a billion people hungry, despite producing enough food to feed 10 billion.

Animal agriculture has a particularly disproportionate impact, producing more greenhouse gas emissions than all forms of transportation combined. Comprehensive analyses of the global farming system, assessing ‘farm to fork’, show that shifting towards plant-based diets would have the biggest impact on planetary health than any other driver of climate change.

Animal agriculture is also the leading driver of species extinction. We are already in the sixth mass extinction event with more animal and plant species at risk of extinction than ever before. Shockingly, there has been more than a 70% decline in wildlife population over the last 50 years.

The food system is also a major driver of antibiotic resistance and pandemic risk. Globally, 40–70% of antibiotics are used in animals, contributing significantly to antibiotic-resistant infections in humans. More than one million people die from antibiotic-resistant infections around the world annually, and a UK Government review estimated that this may rise to 10 million by 2050. One of the review’s key recommendations is to reduce antibiotic use in animal agriculture.

Food-borne infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, despite the widespread use of antibiotics in animals. Most infections are due to animal- or plant- foods being contaminated by the manure of food animals. In 2010 there were 582 million cases of infection caused by contaminated food, with 351,000 deaths. In Europe in 2022, there were 140, 241 confirmed cases of Campylobacter infection, usually acquired from eating chickens, and 65,967 cases of Salmonella infection mainly linked to the consumption of eggs.

Diet-related diseases

Suboptimal diets are also responsible for more deaths than any other risks globally, including tobacco smoking. Diet-related disease and deaths account for a quarter (26%) of all adult deaths each year; the proportion of premature deaths attributed to dietary risks is highest in Northern America and Europe (31% each), and lowest but also at notable levels in Africa (17%). These deaths are predominantly due to cardiovascular disease, cancer and type 2 diabetes.

No region of the world is meeting recommendations for healthy diets. A review of global diets in 195 countries found that diets are too high in processed and animal-derived foods and insufficient in healthy plant foods. Fruit and vegetable intake is still about 50% below the recommended level of five servings per day that is considered healthy, and legume and nuts intakes are each more than two thirds below the recommended two servings per day. In contrast, red and processed meat intake is on the rise and almost five times the maximum level of one serving per week. The consumption of sugary drinks, which are not recommended in any amount, are also rising.

In the UK, 18,000 premature deaths are caused every year by not eating enough vegetables and legumes. The most recent UK national dietary data shows that only 9% of 11-18 year-olds meet the five-a-day fruit and veg target, and only 4% of adults meet the recommended fibre intake. Additionally, almost a third of men aged 19-64 consume more than 90 grams per day of red and processed meat, well in excess of recommended limits. Household income impacts fruit and vegetable consumption with the poorest households eating almost one less portion a day compared to the richest households.

What does a healthy and sustainable diet look like?

Shifting towards plant-based diets has clear, combined benefits for human and planetary health. Such diets can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 75% and lower other environmental impacts of the food system by more than 50%. This is largely because producing animal-based foods is a highly inefficient process: meat and dairy production uses 83% of farmland and produces 60% of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, while only providing 18% of calories and 37% of protein. Even the production of meat and dairy with the lowest environmental footprint is less sustainable than the worst-performing plant food source.

At the same time, plant-based diets can improve nutritional quality and significantly reduce the burden of chronic disease, reducing premature mortality by 22%. A 2022 study by Clarke at al. showed that animal derived foods have a greater environmental impact than plant-based foods, and that more nutritious foods tend also to have a lower environmental impact, confirming we don’t need to compromise on our personal health to support planetary health.

EAT-Lancet and the Planetary Health Diet

In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission developed global scientific targets that bring together recommendations for a global healthy reference diet, produced from sustainable food systems, to ensure that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Paris Agreement are achieved. In October 2025, the EAT-Lancet commission was updated to more centrally consider the importance of a just food system. This is a food system that’s fair for all people, from fair wages to healthy food access.

The recommendations for the reference diet remained largely the same.

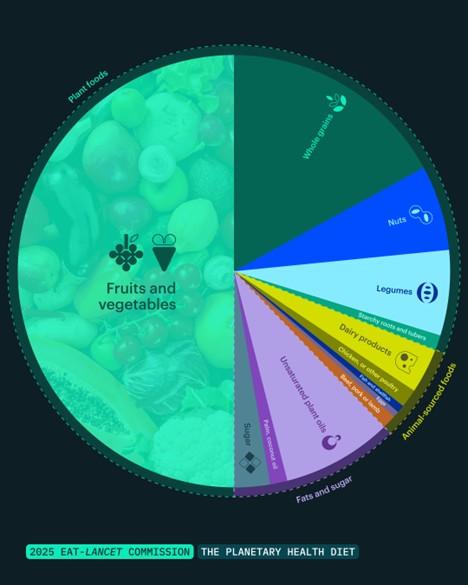

The reference diet, termed The Planetary Health Diet (PHD), consists mainly of whole plant foods, with low amounts of animal-derived, unsaturated fats rather than saturated fats, and limited refined grains, processed foods, and added sugars, as shown in Figure 1 below. Meat and dairy is considered optional and if consumed should provide less than 15% of total calories. A shift to the PHD requires a more than doubling in the consumption of healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts, while the consumption of less healthy foods such as added sugars and red meat will need to be reduced by more than 50%. This will primarily involve reducing excessive consumption in wealthier countries. Adoption of the Planetary Health Diet could prevent up to 15 million deaths per year globally, and could reduce type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer risk, and all-cause mortality. It’s important to note that the PHD is based entirely on the effects of diet on human health, not on the environment; environmental impacts were considered after the diet was developed for optimal human health.

The 2025 report quantifies the global food systems’ share of all nine planetary boundaries. It confirms that current food systems are the single most influential driver of planetary boundary transgression, driving the transgression of 5 of the 7 breached boundaries. By adopting the PHD it’s possible to keep the global food system within planetary boundaries, and could reduce all food-related emissions by half, alongside reductions in land use, and freshwater consumption. Scientists have estimated that it would also decrease antimicrobial use by approximately 42% due to the reduction in animal-sourced foods.

The Planetary Health Diet is not a rigid prescription. It’s designed to be flexible and compatible with a wide range of cuisines and cultural preferences. This includes traditional and evolving healthy eating patterns that align with modern lifestyles and time constraints. As healthcare professionals advocating for the PHD, it’s important that we work with local communities to provide dietary advice that is culturally appropriate and fits within individuals’ realities. It does however reconfirm that animal-sourced foods are not essential in the diet and a 100% plant-based or vegan diet, when appropriated planned and supplemented, is compatible with the recommendations.

Figure 1, The Planetary Health Plate. From the Summary Report of the EAT-Lancet Commission 2025, Available at: https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet/summary-report/

The global dietary shift is one part of the EAT-Lancet ‘bundle’ set of actions that are outlined and need to be taken together in order for the food system to simultaneously remain within all planetary boundaries and meet the scientific targets for healthy diets and sustainable food production. As well as a shift towards plant-based dietary patterns, we also need to see dramatic reductions in food losses and waste, and major improvements in food production practices.

Do plant-based diets risk nutrient deficiencies?

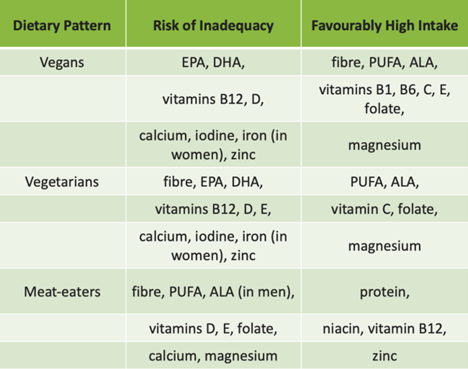

It’s a common albeit overstated concern that plant-based diets, such as the Planetary Health Diet, increase risk of nutrient deficiencies. In 2021, a systematic review of 141 observational and intervention studies aimed to assess the nutritional adequacy of meat-based diets compared to plant-based diets (mainly vegetarian and vegan). All diet patterns had nutritional inadequacies, as shown in Table 1 below. Meat-eaters were at risk of inadequate intakes of fibre, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), folate, vitamin D, E, calcium and magnesium. Vegetarian and vegans had lower intakes of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium and lower levels of bone turnover markers than meat eaters. Vegans had the lowest vitamin B12, calcium and iodine intake, and also lower iodine status and lower bone mineral density. Fibre, PUFAs, folate, vitamin C, E and magnesium intakes were high in plant-based diets. Average fibre intake amongst vegans was 44g/d compared to 28g/d in vegetarians and 21g/d in meat eaters. All diet groups met protein and energy requirements.

Table 1, showing the nutrients at risk of inadequacy in vegan, vegetarian, and omnivorous diets from Neufingerl and Eilander 2021.

When reducing animal-derived foods, it’s crucial that individuals consume a diverse range of plant foods, particularly a sufficient intake of legumes, nuts, and seeds, as well as calcium- and iodine-fortified dairy alternatives to meet nutrient requirements and reduce the risk of inadequate nutrient intakes.

While it’s important that diets meet micronutrient requirements, healthcare professionals should avoid focusing too narrowly on individual nutrients and instead, focus on a whole diet approach. Diverse, balanced, minimally processed, and plant-rich dietary patterns should be the focus for meeting dietary needs, and are the best foundation for achieving both nutritional adequacy and sustainability.

Certain population groups may need to pay particular attention to specific nutrients. For instance, women of reproductive age should ensure adequate iron intake, while older adults may benefit from prioritising high-quality protein to support muscle and functional health. Particularly in these cases, food fortification and supplementation can be beneficial solutions to meet micronutrient requirements in specific target groups.

Fish consumption, health, and sustainability

Recommendations for fish consumption are where health and environmental considerations diverge. Most dietary guidelines recommend fish consumption once or twice a week, including the 2025 EAT-Lancet Commission reference diet. The regular consumption of fish does have positive health impacts, predominantly because it is replacing other less healthy foods, such as red and processed meat in the diet, and is a source of unsaturated fats, including long chain omega-3 fatty acids.

Whether the addition of fish to a predominantly plant-based diet improves health outcomes above and beyond the benefits of eating whole plant foods is not known. However, it is not thought to be necessary and nutritional requirements can be met without consuming fish. Essential long chain omega-3 fatty acids are the mostly commonly cited reason for continuing to consume fish. However, they can be obtained straight from the source, marine algae, or from the precursor short chain omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid, found in plant-foods, including walnuts, chia and flax seeds.

For a global population of over 8 billion to eat fish 1–2 times a week is unlikely to be sustainable given that 90% of world fish stocks are fully or over-exploited from fishing. In addition, there are concerns over mercury and other fat-soluble pollutants (polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins) contamination of fish and shellfish, particularly larger fish that are higher up the food chain. Mercury in particular is associated with neurological toxicity.

Co-ordinated backlash to EAT-Lancet 2019

The acceptance and success of EAT-Lancet was corrupted by a coordinated industry and influencer online campaign against the report.

In April 2025, an exposé by DeSmog uncovered that the PR firm Red Flag, working on behalf of the Animal Agriculture Alliance, orchestrated a global backlash against the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet. The Red Flag campaign coordinated talking points, media briefings, and online attacks to discredit the recommendations as “radical”, “out of touch” and “hypocritical”. Much of the attack converged around the hashtag #Yes2Meat, which reached 26 million people on Twitter (now X), more than the 25 million who were reached by posts promoting the research. The negative campaign successfully moved ‘undecided’ users and critical posts were shared 6 times more frequently than supportive ones.

In September 2025, research by the Changing Markets Foundation revealed the social media backlash was the result of a web of a “coordinated network of mis-influencers”, with some having clear links to the meat industry.

Unfortunately, we can expect the same type of response to EAT-Lancet 2.0, the full report lays out the types of tactics likely to be used and some key trends that might negatively impact EAT-Lancet 2.0. As trusted nutrition and healthcare professionals we must do what we can to counteract mis- and disinformation in response.

Other considerations for a sustainable diet

A sustainable diet is more than just optimal for health and the environment, other socioeconomic factors are just as important. The Food and Agricultural Organization definition includes aspects of food and nutrition security, cultural acceptability, accessibility, economic fairness and affordability.

The EAT-Lancet 2025 Commission also more centrally focuses on justice in the food system, integrating distributive, representational, and recognitional justice within a human rights framework that includes the rights to food, a healthy environment, and decent work.

Current levels of food waste are also unsustainable. For example, the food waste in the EU is more than 59 million tonnes a year, with more than half generated in the home. Globally, approximately a third of food is wasted across the supply chain with 70% of this waste occurring in the home. Reducing food waste is also critical for reducing emissions from the global food system.

Cost of a healthy diet

Most studies show that a healthier, more sustainable diet would not be more expensive than current diets and may even be cheaper. Modelling from the UK shows that a shift towards a diet more in line with the Eatwell Guide would not significantly alter cost. Similarly, a study from Australia showed that shifting to the Planetary Health Diet could be cheaper than the current diet of metropolitan-dwelling Australians.

Another study compared the cost of seven sustainable diets to the current typical diet in 150 countries. The results showed that in high-income countries, vegan diets were the most affordable and reduced food costs by up to one third. Vegetarian diets were a close second. Flexitarian diets with low amounts of meat and dairy reduced costs by 14%, whereas pescatarian diets increased costs by up to 2%.

Nonetheless, we have to appreciate that healthy diets are not affordable for low income families. The Food Foundation’s The Broken Plate 2025 report shows that the poorest fifth of UK households would need to spend 45% of their disposable income on food to meet government-recommended diet, rising to 70% for households with children. This compares to just 11% for the richest fifth. This is where we need to find local solutions to ensure healthy and sustainable diets are in fact affordable for all.

EAT-Lancet 2025 recommends that healthcare professionals should “train to be able to deliver empathetic, equity-informed nutrition care across the whole socioeconomic spectrum. This includes screening for access barriers, such as food insecurity, price and time constraints, income, gender, or social inequities.”

Health professionals can act now

The good news is that we can each make a positive contribution – the power is on our plate and healthcare professionals have a key part to play.

The international community has called Health Professionals to action. The EAT-Lancet commission urges health professionals to consider both health and environmental sustainability when counselling patients about diet and recommends advising the shift to more plant-based diets. You can:

- Advocate for healthy, sustainable meals in your healthcare institution. This shapes patient experience, can showcase what healthy, sustainable meals can look and taste like. Visit Plants First Healthcare to find out more about what you can do as a healthcare professional or member of the general public.

- Use your trusted position as a healthcare professional to counter misinformation about nutrition, advocate for evidence-based policies and a health system and food environment that is free from undue influence

- Use the EAT-Lancet Action brief for healthcare professionals and the Toolkit for plant-based catering at conferences and events.

Additionally, the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) have published a “Declaration Calling for Family Doctors of the World to Act on Planetary Health”. This involves advising patients to transition to a more plant-based diet in line with the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet.

Finally, this fantastic tool from Our World in Data allows you to assess the environmental impact of your food choices.