A review of the week’s plant-based nutrition news 8th January 2023

Happy new year to you all. Welcome to the 10th anniversary of the Veganuary campaign and the international year of millets. I start the year with a reminder that plant-based diets are front and centre of clinical guidelines for prevention and management of chronic conditions.

It may seem that a vegan or plant-based diet is not the ‘go to’ dietary recommendation for the medical community. Yet, all health-promoting diets share in common a handful of key features that are entirely compatible and consistent with a 100% plant-based diet. These common features include an emphasis on minimally processed fruit, vegetables and whole grains, whilst favouring plant sources of protein from beans, lentils, pulses, chickpeas, soya, nuts and seeds. Healthy diet patterns also minimise or avoid processed and unprocessed red meat, ultra-processed foods, refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverages. A whole food plant-based diet (aka a healthy vegan diet) meets all these basic criteria and we know that such a diet is suitable for all ages and stages of life.

Below I highlight guidelines and recommendations from the international medical community that showcase the positive impact of a healthy plant-based diet on a variety of health conditions.

OPTIMAL NUTRITION FOR CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the general term given to a group of disorders that affect the heart and blood vessels. The INTERHEART and the INTERSTROKE studies demonstrated that modifiable lifestyle and psychosocial factors were responsible for 90% of the risk of developing a heart attack or stroke. Therefore, our approach to reducing the incidence and mortality from these conditions should focus on addressing these risk factors. This practice statement from the American Society for Preventive Cardiology brings us up to date with the evidence on the optimal nutritional approach for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

The evidence really hasn’t change for decades but has strengthened through the availability of additional studies. Health professionals should recommend a plant-predominant diet centred around foods that promote health and prevent atherosclerosis i.e. fruit, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds and fatty fish. The recommendations can be met by following a Mediterranean, DASH (dietary approaches to stop hypertension), healthy vegetarian or exclusively plant-based diet. The main difference between these diet patterns is the amount of animal products included, with the Mediterranean and DASH diet patterns including fish, lean meats and low fat-dairy. They share in common the minimisation of processed meats, refined carbohydrates and sugar-sweetened beverages, limiting the amount of dietary cholesterol and sodium, replacing saturated fat with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, and avoiding trans fats.

The guidelines do continue to recommend the consumption of fatty fish without addressing the environmental sustainability of this approach. The benefit of consuming fish appears to be mainly a substitution effect (if you are eating fish you are generally eating less of other types of animal flesh) and the long-chain omega-3 content (DHA/EPA). Algae-derived omega-3, the primary source for fish, has a similar effect on blood omega-3 levels as the consumption of fish and plant-exclusive/healthy vegan diets have significant benefits for cardiovascular health. The additional benefit of fish is yet to be established.

The guidelines warn against an animal-based low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diet given the adverse impact on long term cardiovascular health. In theory, a low-carbohydrate plant-based approach may be beneficial but there are no long-term studies with hard clinical outcomes. In addition, there is no strong evidence that intermittent fasting has additional benefits to calorie-restricted diets for weight loss or cardiometabolic health.

I am pleased to see paediatric nutrition included and the negative impact that socioeconomic disparities and racism can have on access to healthy nutrition and consequent health outcomes.

DIETARY GUIDELINES FOR CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH: These guidelines from the American Heart Association are very similar to those from the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. There is an emphasis placed on dietary patterns rather than individual foods or nutrients and the report highlights the essential role of healthy nutrition from early life.

The key elements of a heart healthy diet pattern include the ability to maintain a healthy weight and that it is centred around fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Protein should be obtained mostly from plants (legumes, including soya, and nuts) and processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, tropical oils and animal fats should be minimised, whilst also limiting the use of added salt and avoiding alcohol. Fish, seafood and low fat dairy is still considered compatible with a heart healthy diet but the guidelines infer that meat and poultry are not necessary in the diet and ‘if desired’ should be lean cuts with processed meats best avoided. There is a cautionary note for plant-based meat alternatives, which are often highly processed and high in salt.

An emphasis is placed on replacing saturated fat and trans fat (including that found in meat and dairy) with unsaturated sources of fat (from whole plant foods such as nuts and seeds and also non-tropical vegetable oils). I am pleased that the report is clear that alcohol should not be consumed and intake should be limited or avoided.

This type of heart healthy diet pattern is also noted to be beneficial for the prevention of type 2 diabetes, kidney failure and cognitive decline. In addition, there is an emphasis placed on the environmental impact of our diet choices, noting that healthy vegetarian diets are not only heart healthy but consistently associated with a lower environmental footprint. The guideline pays attention to the societal and cultural challenges that prevent people from adopting healthy diet patterns, including socioeconomic factors, food insecurity, structural racism and food industry marketing of unhealthy foods. The report notes that public health interventions are required to ensure healthy food is affordable and accessible too all.

Overall, a very good guideline which certainly features plant foods at its core and it entirely compatible with consuming a healthy whole food plant-based diet.

PREVENTION OF DEMENTIA: In their 2017 report, the Lancet Commission reported that 35% of cases could be prevented through modifiable lifestyle risk factors. These risk factors include tobacco smoking, physical inactivity, depression, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hearing loss and social isolation. The updated report from 2020 adds 3 further risk factors; excessive alcohol consumption, air pollution and traumatic brain injury. By addressing this 12 risk factors it is predicted that up to 40% of cases of dementia could be prevented or delayed. It should be noted that the studies informing these recommendations are mostly performed in high income countries, whereas the burden of dementia is greater in low and middle income countries and therefore the potential for prevention may be even greater.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends a Mediterranean diet pattern and adherence to the WHO healthy eating guidelines as described below:

A healthy diet includes the following:

- Fruit, vegetables, legumes (e.g. lentils and beans), nuts and whole grains (e.g. unprocessed maize, millet, oats, wheat and brown rice).

- At least 400 g (i.e. five portions) of fruit and vegetables per day, excluding potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava and other starchy roots.

- Less than 10% of total energy intake from free sugars, which is equivalent to 50 g (or about 12 level teaspoons) for a person of healthy body weight consuming about 2000 calories per day, but ideally is less than 5% of total energy intake for additional health benefits. Free sugars are all sugars added to foods or drinks by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates.

- Less than 30% of total energy intake from fats. Unsaturated fats (found in fish, avocado and nuts, and in sunflower, soybean, canola and olive oils) are preferable to saturated fats (found in fatty meat, butter, palm and coconut oil, cream, cheese, ghee and lard) and trans-fats of all kinds, including both industrially-produced trans-fats (found in baked and fried foods, and pre-packaged snacks and foods, such as frozen pizza, pies, cookies, biscuits, wafers, and cooking oils and spreads) and ruminant trans-fats (found in meat and dairy foods from ruminant animals, such as cows, sheep, goats and camels). It is suggested that the intake of saturated fats be reduced to less than 10% of total energy intake and trans-fats to less than 1% of total energy intake. In particular, industrially produced trans-fats are not part of a healthy diet and should be avoided.

- Less than 5g of salt (equivalent to about one teaspoon) per day. Salt should be iodised (salt is not iodised in the UK).

The evidence currently does not support the use of any dietary supplements for prevention of dementia.

There are limited data on fully plant-based diets and risk of dementia. The only study we had for a while was a preliminary report from the Adventist Health Study suggesting that meat eaters had a significantly higher risk of developing dementia compared to vegetarians. A recent publication analysed data from the prospective Tzu Chi Vegetarian Study. It included data from 5710 participants who were aged 50 years or older at the time of recruitment in 2005 and followed till 2014. The participants were all Buddhist volunteers, 3154 were non-vegetarian and 1737 were vegetarian. During the average follow up of 9.2 years there were 121 cases of dementia (37 vegetarians and 84 non-vegetarians) identified and vegetarians had a 33% reduction in the risk of dementia. Subgroup analysis found that vegetarians were specifically protected against dementia under the age of 75 years.

You can read more about a healthy diet and lifestyle for prevention of dementia here.

CANCER PREVENTION: Plant-based diets are front and centre of cancer prevention guidelines. The most up to date analysis finds that 44% of cancers could be prevented by addressing modifiable risk factors, both behavioural and metabolic. The leading risk factors are tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and carrying excess body weight. I always find it strange how there is so little acknowledgement about the fact that preventable chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and inflammatory/autoimmune diseases are associated with an increased risk of cancer. Unfortunately, rates of preventable cancers continue to rise.

Prevention guidelines clearly recommend a diet centred around healthy plant foods; fruit, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds. These are the only foods associated with a lower risk of cancer, prevention of other chronic conditions and minimises exposure to food-related cancer-causing agents.

WHOLE FOOD PLANT-BASED DIET FOR WEIGHT MANAGEMENT: After several years of campaigning, health professionals in New Zealand have been successful in getting recommendations for a whole food plant-based diet incorporated into national guidelines on weight management. The guideline acknowledges that there are several diet patterns that can support weight loss, but the key principles of an appropriate diet pattern are that it is healthy, i.e. balanced, nutritious and meets energy requirements, and that is can be maintained in the long-term. A whole food plant-based diet meets these requirements and is associated with the ability to maintain a healthy weight with ageing. So it is only right that this new revised version includes a section on the use of a whole food plant-based diet to support long-term weight management. It states that a whole food plant-based diet is a ‘Long-term sustainable method of significant body weight reductions despite no caloric or portion size restrictions’. The guideline also acknowledges the benefits of a whole food plant-based, vegetarian and vegan diet for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors and for reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes.

This is a really positive step forward and I hope other national and international guidelines will also be updated to recognise the importance of plant-based diets for supporting optimal health. Read more about why a plant-based diet is so good for weight management in my article here.

TYPE 2 DIABETES REMISSION: Not only is type 2 diabetes preventable in most people, it is possible to achieve remission even after a diagnosis of diabetes and should be the goal of treatment. Remission is defined as HbA1c <6.5% for at least 3 months with no surgery, devices, or active pharmacologic therapy for the specific purpose of lowering blood glucose. This guidelines from 2020 provides a summary of the available evidence. Diabetes remission usually requires significant weight loss, which can be achieved through various approaches, including bariatric surgery and very low calories diet. Dietary interventions should be considered the first line approach and these need to be intensive enough to result in substantial weight loss, restore beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. The American College of Lifestyle Medicine’s favoured approach is a whole food plant-based diet given that this by default produces a calorie deficit, is health promoting and has long term benefits for health. The authors state ‘A WFPB diet has multiple benefits of minimizing harmful foods, emphasizing healthy foods, reducing energy density through lower levels of fat and higher amounts of fruits, vegetables, and water. It also facilitates weight loss without feelings of deprivation or hunger, and seems well-tolerated by patients’.

DIETARY INTERVENTIONS FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES REMISSION: This expert consensus statement has reviewed all the evidence on dietary interventions and has come up with a recommendation for the optimal dietary approach taking into account short and long-term impacts on health outcomes, plus adherence and sustainability. The authors concluded that, ‘Diet as a primary intervention was considered most effective when emphasising whole, plant-based foods including whole grains, vegetable, legumes, fruits, nuts and seeds, with minimal consumption of meat and other animal products’. It is well worth reading the full document, which is open access.

Read my updated summary on the role of plant-based diets in prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes.

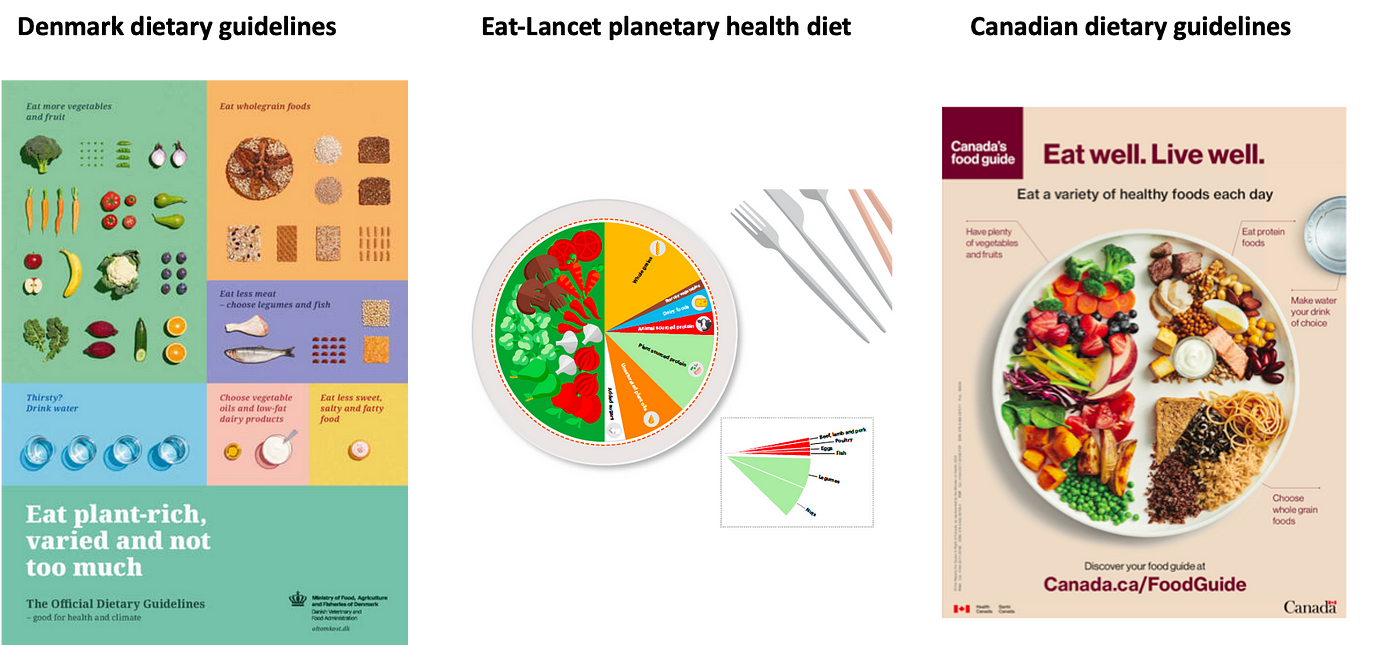

INTERNATIONAL DIETARY GUIDELINES: As country-based guidelines are updated, they are being adapted to include recommendations that support both human and planetary health. This means supporting citizens to shift towards a predominantly plant-based diet with the option of a 100% plant-based diet if desired. I highlight the 2019 Health Canada dietary guidelines that removed dairy as a food group and recommend choosing plant sources of protein in preference to animal foods. The Denmark dietary guidelines also recommend ‘Eat plant-rich, varied and not too much’.

The 2019 Eat-Lancet commission recommends a plant-predominant diet, limiting energy from animal foods to only 13.5%. The recommendation states ‘Healthy diets have an appropriate caloric intake and consist of a diversity of plant-based foods, low amounts of animal source foods, unsaturated rather than saturated fats, and small amounts of refined grains, highly processed foods, and added sugars’. The authors highlight that the guidance is entirely compatible with a vegan diet and that vegetarian and vegan diets have significantly lower impacts on the environment when compared to diets that include fish and meat.

In 2021, The WHO produced a review of plant-based diets. The report acknowledges that consumers may not want to completely eliminate animals foods in the diet, however, any incremental reduction in consumption would be beneficial. It clearly states that a 100% plant-based diet is healthy and nutritionally adequate when well planned. The report concludes ‘considerable evidence supports shifting populations towards healthful plant-based diets that reduce or eliminate intake of animal products and maximise favourable “One Health” impacts on human, animal and environmental health.’

SUPPORTING PATIENTS: Healthcare professionals have been called to action. The climate and ecological crisis is also a health crisis. One of the required solutions is to adopt a plant-based diet and as trusted members of society, healthcare professionals are well placed to support this transition through their interactions with patients and their communities. However, we hear all the time that doctors and allied health professionals learn very little clinical nutrition in their training and even the nutrition and dietetic professions have curricula based about around the typical omnivorous diet, with plant-based diets only being discussed in the context of ‘restrictive diets’ and ‘risk of nutritional deficiencies’.

Health professionals don’t need to be experts, but we do need to understand the basics of a healthy, nutritionally adequate, plant-based diet. The article highlighted summarises some easy recommendations to support patients on their journey and sign posts to reputable resources (i.e. PBHP UK !).

Please follow my organisation ‘plant-based health professionals UK’ on Instagram @plantbasedhealthprofessionals and facebook. You can support our work by joining as a member or making a donation via the website.